Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Induced New Legal and Governance Dilemma: Deepfake Something Very Near to Most Propelling Change: Deepfake Audio, Deepfake Video, or Image Created by Artificial Intelligence, Which Are Almost Perfectly Believable but Are Actually Generated. Well-intentioned as they often were, the applications beneficially used in filmmaking, education, and digital art creation have been misused for various ends: invasion of privacy, non-consensual pornography, financial fraud, and political misinformation that all undermine public trust and democratic integrity. Deepfake incidents are on the rise in India, and as such, there is no specific and independent law to govern them. The Information Technology Act, 2000, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 are, at this point, the only legislation governing these issues, but they give only limited protection as the technologies evolve. The paper advocates for deepfake-specific legislation that keeps the balance among innovation, privacy, and safety, in addition to trust in democracy.[1] And uses doctrinal, comparative, and analytical techniques to broaden this. Such legislation will ensure that technologies serve the common good without suffering compromise against truth or justice in the public interest.

Keywords: Deepfakes, Artificial Intelligence, Indian Cyber Law, Privacy, Platform Accountability, Digital Trust.

Introduction

Technology has always shaped how information is created, shared, and consumed. Today, one of the most disturbing developments driven by AI is the deepfake: synthetic audio, video, or images of real individuals generated using machine learning. While they can enhance creativity in education, entertainment, and accessibility, their dangers are far greater. Deepfakes have been used for non-consensual pornography, political propaganda, impersonation of celebrities, and financial fraud. By blurring the line between truth and falsehood, they threaten not only individuals but also democracy, journalism, and digital trust.[2]

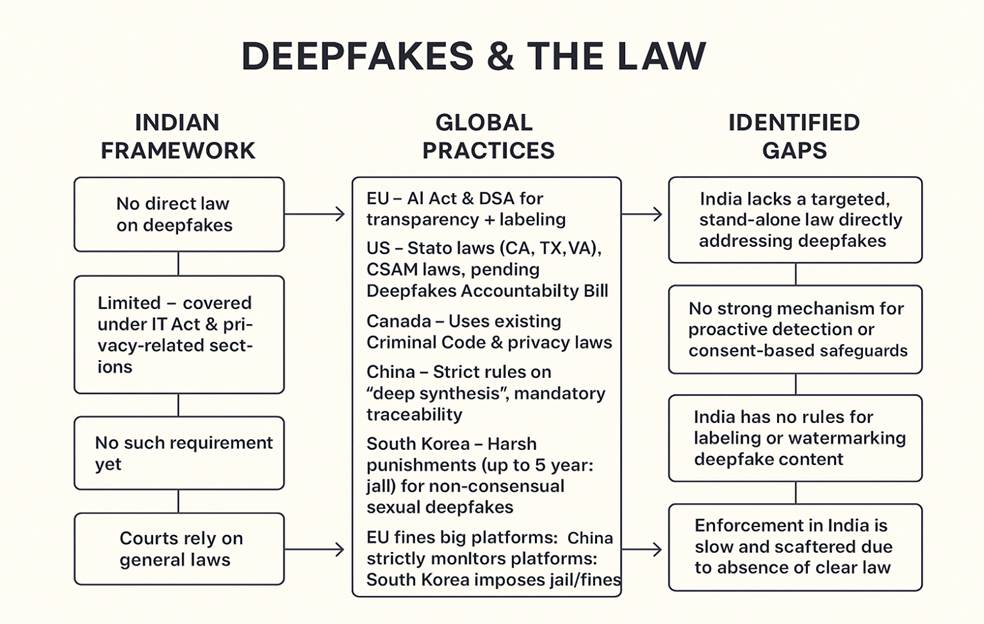

India has witnessed cases ranging from manipulated political speeches to explicit fake videos of celebrities and private individuals. Such incidents highlight the urgency of legal intervention. Yet, Indian law lacks a specific statute addressing deepfakes. Law enforcement relies on sections of the IT Act, 2000, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. These provide some protection against defamation, obscenity, or misuse of personal data, but were never designed to regulate deepfakes. As a result, enforcement remains slow, and platforms face limited liability.

Globally, regulators are more proactive. The European Union’s AI Act mandates transparency and labeling of AI-generated content. China’s Deep Synthesis Regulations require watermarking, authentication, and prompt removal of manipulated content. Several U.S. states criminalize the use of deepfakes in elections and non-consensual pornography. These examples underline that deepfakes require targeted legislation, not patchwork reliance on general laws. India must similarly create a clear legal framework to safeguard both individual rights and democratic integrity.

Research Question

If India’s current legal framework is insufficient to address the harm caused by deepfakes, what specialized legislation is required to balance innovation, privacy, safety, and democratic trust?

Research Methodology

The study employs a doctrinal, comparative, and analytical approach. The doctrinal method includes many Indian statutes along with their case laws and policies by the government pertaining to the Information Technology Act, 2000, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. Secondary materials like books, research papers, and credible reports also receive a mention in this study.

The comparative method looks at world approaches, including the EU AI Act, China’s Deep Synthesis Regulations, and U.S. state laws, to find best practices that best suit India. The third method is an analytical one, outlining all the lacunae in the available Indian framework, thus paving the way for reforms.[3].

The research is completely qualitative in its methodology; its direct reflection is in the legal interpretations as opposed to empirical data. With such methodology, one can gauge how the various aspects of existing law govern deepfake misuses and can establish the need for a dedicated deepfake law in India that strikes a balance between free speech, privacy, and innovation.

Literature Review

The evils and positives of deepfake technology are widely acknowledged by scholars; it can be very creative but can also be opposed to education and even healthcare, posing a greater threat to privacy, democracy, and security.

Dami (2022)[4]In Analysis and Conceptualization of Deepfake Technology as a Cyber Threat, ” it is stated that when such basic tools are incorporated in popular editing apps, they can be advanced in their legal use for satire, parody, or movies such as Rogue One. The negative uses of sextortion, revenge pornography, cyberbullying, biometric hacking, identity theft, and psychopathy posing threats to a nation’s security present far larger challenges. Since anyone can be manipulated using just a single picture, such challenges will appear for any victim when it comes to proving manipulation. Dami has stressed that what is needed apart from legal sanctions are stronger accountability of the platforms, digital literacy, and public awareness.

It was on similar lines that Korshunov and Marcel.[5] (2021) conducted tests on 120 Facebook videos on 60 subjects. Just 24.5% managed to identify deepfakes even in the hardest case, and even sophisticated models did poorly; this was indicative of how convincing and difficult to trace deepfakes have just become.

In the Future of Deepfakes: Need for Regulation essay, Gupta[6] (2023) made an analysis, contrasting responses from the EU, the U.S., and China. Agreeing to the benefits of healthcare, he marked a delay in the regulations regarding non-consensual pornography and political misuse. He encouraged an international cooperative effort with AI-based detection tools and awareness campaigns.

This risk is similarly popular among Indian scholars. Kothari and Tibrewala[7] (2024) have warned that altered evidence could erode the criminal justice system due to planting doubt in the minds of witnesses or convicting wrongly. True, some protections do exist in the IT Act, 2000; DPDP Act, 2023; and Bharatiya SakshyaAdhiniyam, 2023, but none of these directly criminalize deepfakes. Clear legislation and judicial training have been recommended. Vig (2024)[8]Also found that the legal framework in India was inadequate. He stated that the Copyright Act, 1957, and the criminal provisions do not cover the misuse of deepfakes. He advocated literacy programs and detection mechanisms in accordance with initiatives such as WEF’s Digital Trust Initiative and the EU’s Horizon 2020.

Outside India, Abidin (2023) studied deepfake pornography in Indonesia, revealed how platforms like FaceApp disclaim counter liability in an event where the application is misused, and advocated for the accountability of such platforms and stricter penalties. A study by Springer (2025)[9] Identified dataset bias and huge computational costs as barriers to detection. Moreover, the HAV-DF dataset in India showed that detectors trained in English failed in multilingual contexts, exposing linguistic bias. New defenses, such as adversarial feature similarity learning, are improving resilience; detection tools today are 95% accurate concerning fraud prevention and real-time audio verification.

Recent works from India are reminding us of the need for change. Yadav (2024)[10]Asserted that deepfakes are not recognized in statutes today, leading to inconsistent enforcement, whereas some other scholars insisted on hybrid legal models balancing free speech and dignity. TIJER Journal (2024[11]) drew attention to the electoral threat posed by deepfakes and called for transparency, labeling, and platform liability. Regulation is advancing globally currently; the EU AI Act (2025) calls for transparency, while the US Take It Down Act ensures swift removal of sexual deepfakes. Countries such as China, South Korea, and the UK have criminalized or restrained harmful uses.

Corporate misuse, indeed, demonstrates the financial dangers. Deepfake CEO scams accounted for losses of over $200 million from U.S. companies in 2024; thus, an increased need to raise corporate protection levels, train personnel, and strengthen verification systems.

Analysis and Findings

- Indian Law Framework

India doesn’t have a separate law related to deepfakes, and the word is not defined in any statute under Indian law. However, some laws can be used in cases of abuse. As per the Information Technology Act, 2000[12]Section 66E penalizes the violation of privacy by intentionally capturing, publishing, or transmitting private images without consent. Section 67 of that Act deals with the prohibition of transmission in electronic form of obscene material or sexually explicit material. Likewise, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023[13], which took the place of the IPC, provides remedies for defamation, reputational damage, and obscenity under situations where the deepfake content acts to diminish dignity and reputation.

Apart from these laws, enforcement is going to be very difficult in the absence of any special law. The courts have started recognizing the issues, ever since the actor Anil Kapoor was given some relief regarding unauthorized deepfakes; however, the judiciary still awaits a clear legal framework that will assist in deterrence and attribution of liability.

- International Regulatory Framework

European Union (EU)

In the act of the European Union, certain deepfake usages are categorized as “high-risk,” with the requirement to disclose whenever the content is generated by AI. With the Digital Services Act (DSA), platforms are obliged to label manipulated media and inform users, with the Code of Practice on Disinformation telling platforms to engage in curbing such fabricated content with liability for heavy fines.

United States (US)

The United States does not have a minor federal law regarding deepfakes, but uses existing child sexual abuse material (CSAM) statutes to criminalize deepfake-child pornography. California and Texas outlaw deepfakes that pertain to elections; Virginia, in addition, criminalizes nonconsensual pornographic deepfakes. What should suffice at the federal level is President Biden’s AI Executive Order instructing the Commerce Department to develop watermarking standards, as well as the recently introduced Deepfakes Accountability Bill of 2023, which aims to make AI content label requirements.[14]

Canada

There’s no specific deepfake legislation in Canada yet. The harmful uses of these artificial images can be prosecuted under the Criminal Code provisions on harassment, voyeurism, and defamatory libel. Privacy laws also give protection from unauthorized use of a person’s image or likeness, but legal experts believe that there should be direct, modern legislation so that deepfake-related harms can be more accurately addressed..

China

China has imposed tough regulations on deepfake material. All content generated with “deep synthesis technology” must be traceable in any case where developers will need to act in accordance with local laws and principles, making sure that their work does not spread disorder or misinformation.[15] This is a hard-hitting statement reflecting a strong state-led approach of China to control deepfakes.

South Korea

Non-consensual sexually explicit deepfakes are criminal offences in South Korea, with a maximum penalty of 5 years imprisonment or 50 million won as a fine. These punishments are intended to safeguard citizens against the malicious use of deepfakes and, hence, indicate the country’s firm commitment towards privacy concerns and dignity protection.[16]

- CASE LAWS RELATED TO DEEP FAKE LAWS IN INDIA

Anil Kapoor versus AI Deepfake (2023)[17]

Bollywood’s Anil Kapoor moved the Delhi High Court by filing a case after coming upon the use of his face and voice in making GIFs, ringtones, and porn. The aforementioned court successfully restricted 16 persons from monetizing Kapoor’s name, image, and likeness (NIL) soon after. It was held that nobody had the right to exploit another’s personality. The case accentuated the existence of personality rights for celebrities vis-à-vis AI misuse.

Rana Ayyub v. Internet Harassment (2018)[18]

Journalist and activist Rana Ayyub was created into deepfake pornographic videos based on her images. After she spoke about the Kathua rape case, edited videos, and abusive tweets spread worldwide, which resulted in rape and death threats, besides serious psychological distress. At that stage, India had no particular law against deepfakes, as recourse was limited in the courts. This has been more disquieting than in the past, as emphasized by rising instances of deepfake porn.

Swami Ramdev versus Facebook, Google & YouTube (2019)[19]

Yoga Guru Swami Ramdev, therefore, went to the Delhi High Court against Facebook and YouTube, among other platforms, for hosting defamatory videos against him. He prayed for worldwide removal from all such platforms and not just in India. The court also agreed to such relief and mandated that once the platform is informed of such materials, they must be removed worldwide. It should also be noted that such material cannot be ignored or bypassed using Section 79 of the IT Act by the companies. This was a landmark ruling in that it imposed accountability on social media platforms and confirmed the power of India’s courts to prohibit such content worldwide.

Karti Chidambaram versus Union of India (2020)[20]

Politician Karti Chidambaram, after deepfake videos of him being displayed on dubious acts, petitioned. Such clips were intended to damage the reputation of Chidambaram and were meant to create political bias against him. The Madras High Court ruled that such deepfakes actually fell under the provisions of laws against defamation as well as cybercrime and directed platforms to act promptly, with respect to such injunctions, on being notified. It also held that freedom of speech cannot justify defamation, pointing out the need for stricter laws against deepfake misinformation.

Indian Legal Measures against Deepfakes

Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act)

Under the Information and Technology Act,[21] In 2000, deepfakes were very much established in context. Violation under section 66E involves punishment for capturing private photographs or videos, for distribution, without consent, and the punishment may go up to three years of imprisonment or a fine of up to ₹2 lakh. Online impersonation and fraud are dealt with in section 66D, which also includes misuse of identity by channels of using deepfakes; therein, it has a maximum punishment of up to three years of imprisonment and a fine of about ₹1 lakh. Then, with pornographic or sexually explicit deepfakes, Sections 67, 67A, and 67B consider publishing or circulation as illegal. An intermediary may also lose its “safe harbor” protections unless it acts promptly on such material. Besides, deepfake content affecting national security, sovereignty, or public order can be blocked by the government, following Section 69A. Section 72 intends to punish the act of distorting or sharing modified private content without sanction, providing up to two years of imprisonment and a fine. Broadly, some harms are suffered in these provisions. However, they are limited in scope and fragmented in terms of coverage when addressing deepfakes.

Copyright Act, 1957

The production of deepfakes frequently supplants existing videos, photographs, or audio protected under copyright. Under the Copyright Act, 1957[22] No authorization can be assumed for using such creative works. Section 51 runs afoul of deepfake work by employing, without permission, copyrighted materials such as film clips or music. Such an Act would, in this case, enable one to seek legal redress for the manipulation or abuse of his original work to create some form of deepfake.

Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986

The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986[23]It restricts the publishing or sending of any material that may be considered indecent or derogatory to women. Hence, the law subjecting deepfakes that sexually edit or abuse the images or videos of women makes the producers and distributors answerable under the law.

Representation of the People Act, 1951

Deepfakes are a threat not just to an individual’s reputation but even to democracy itself. The Representation of the People Act, 1951[24]It comes into play if any manipulated audio or video is being used to try to defame a candidate or party during elections. This is to protect against the electoral process being disrupted through the use of digitally manipulated content.

Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

The freshly introduced Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023[25] Deals directly with the instances of data misuse or abuse. Given that most deepfakes depend on personal images, voices, or videos without consent, this Act will now give individuals the right to safeguard their data. The political implications of the unauthorized use of such data to create an AI-driven deepfake can now be punished. It is also moving the pendulum towards stronger safeguards for privacy in the digital age.

Advisory by Government Ministries

In addition to this legislation, the government has issued other advisories on how to deal with the deepfake problem. The first advisory, for example, came from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting on January 9, 2023[26] Advising media houses to exercise caution in broadcasting any altered or distorted media and mark the edited material as ”Modified” to inform the audience of the change. Following the advisory, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology issued on November 7, 2023[27] Advised social media platforms to detect and remove deepfakes from their portals and comply with their obligations expeditiously under the IT Rules, 2021. They would disable access to harmful content after it is flagged within 36 hours.

Suggestions

Even as early as 2023, India was still lagging behind the rest of the world in terms of laws related to very particular challenges posed by deep fakes. Though it provides partial safeguards, none of the laws, like the IT Act, 2000, the BNS, 2023, and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, have addressed the peculiarities of deepfake threats.[28] Hence, the answer should rather be a combination of both legal and social measures and not merely existing laws.

1. Clear legal definition:India must also bring a deepfake law. Broadly worded mandates are interpreted idiosyncratically by courts and investigators in the absence of coherent standards, resulting in delays and varying decisions. The initial phase in effective regulation, according to the EU’s AI Act and China’s Deep Synthesis Regulations, is the clear articulation of these laws.[29]

2. Special criminalization: Current provisions make the creation of a deepfake an offense of an incomplete non-penal action. According to the observations made by scholars such as Citron and Chesney, even if the wrong doesn’t seem to create immediacy of damage, even in pretending to be another person, confidence and confidentiality are damaged. It must, therefore, be criminalized in India to create and share deepfakes, with exemptions making it legal for research purposes, satire, and legitimate artistic use.[30]

3. Platform accountability: Most deepfakes spread through social media; however, laws today are ultimately based on self-regulatory sincerity about platform behavior. We do need a more powerful regime wherein the platforms should put a watermark, detection, and rapid mechanisms in place. This European Digital Services Act is a good place to start, with platforms in joint liability, and pushed towards detection technology advancement.[31]

4. Improve the Forensic Capacity: Courts scarcely have it easy determining the authenticity of digital evidence, as in Tata Sons v Greenpeace. If India does not institute deepfakes forensic labs, it may admit fakes or deny genuine evidence.[32] The government should prioritize the establishment of national and regional AI-forensic centres with universities and private experts.

5. Awareness and education of the public: Laws alone would be insufficient. The NITI Aayog and UNESCO survey found that most citizens can hardly identify deepfakes. Such awareness campaigns, media literacy programs in schools, and partnerships between NGOs and the government can empower[33] Indians to identify and resist deepfakes. This lessens people’s dependence on courts, but more importantly, improves and prevents whammies.

6. Balancing rights with restrictions:Judgement in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India[34]Advice of caution from the Supreme Court against the absurd regulation of speech and creativity. Hence, any future law on deepfakes would have to clearly stipulate protections, appropriate penalties, and demand supervision by the courts: such safeguards from misuse would at the same time leave space for genuine engineering creativity. Overregulation can not only stifle expression but also innovation, as the Supreme Court warned against in Shreya Singhal versus Union of India. Hence, any forthcoming law on deepfakes would also have to be accompanied by well-defined protection, appropriate punishment, and supervision from the courts. Such safeguards against misuse would similarly enhance opportunity for creativity in engineering.

India needs precisely such a deepfake law. Clear definitions, targeted criminalization, platform accountability, forensic commitment, and public awareness would lead to comprehensive legislation to deal with the extent of the damage. Only such multi-level integrity could ensure the protection of individuals, protection of trust in democracy, and empowerment of courts to rise against challenges of digital disinformation.

Conclusion

Deepfakes are potentially one of the most serious threats of the digital age. Such can be reputational damage, misinformation, and erosion of trust in democracy. The IT Act, BNS, and DPDP Act of India do not, however, contain specific provisions to help cure the malaise because they have only some limited provisions in place. There is a recognition of the issue by the courts and other policymakers, but solutions are apparently scattered.

Global practices imply the need for particular legislation of what deepfakes are, what constitutes malicious use, which should include labeling and the responsibility of platforms. The need to bolster forensic ability in India will emerge from this process, as will the need for digital literacy. Only a multifaceted approach-a combination of law, technology, and awareness-can keep individual dignity, democratic trust, and authenticity of information safe in the digital age.

SUMITTED BY: POOJA CHOUDHARY

4th year

BA.LL.B(HONS.)

QUANTUM UNIVERSITY,ROORKEE

[1] Danielle Keats Citron & Robert Chesney, Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security, 107 Calif. L. Rev. 1753 (2019).

[2] Robert Chesney & Danielle Keats Citron, Deepfakes and the New Disinformation War: The Coming Age of Post-Truth Geopolitics, Foreign Affairs, Jan.–Feb. 2019, at 147.

[3]Ian Dobinson & Francis Johns, Qualitative Legal Research, in Research Methods for Law 18 (Mike McConville& Wing Hong Chui eds., 2d ed. 2017).

[4]L. Dami, Analysis and Conceptualization of Deepfake Technology as Cyber Threat, ResearchGate (June 2022), https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21862.50246 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[5]Pavel Korshunov&Sébastien Marcel, Subjective and Objective Evaluation of Deepfake Videos, ResearchGate (June 2021), https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9414258 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[6]K. Gupta, The Future of Deepfakes: Need for Regulation, 5 NLU Delhi Student L.J. 123 (2023), https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/nludslj2023&id=123 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[7] S. Kothari & S. Tibrewala, AI’s Trojan Horse: The Deepfake Conundrum Under the Criminal Justice System, 4 GLS KALP J. Multidisciplinary Stud. 45 (2024), https://www.glskalp.in/index.php/GLSKALP/article/view/75/75 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[8] S. Vig, Regulating Deepfakes: An Indian Perspective, 17 J. Strategic Security 70 (2024), https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.17.3.2245 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[9]Advancements in Detecting Deepfakes: AI Algorithms and Future, Springer Nature. J. AI & Soc. (2025), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43926-025-00154-0 (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[10]Rishita Yadav, Deepfakes and the Indian Legal Framework: Challenges and Prospects, J. Legal Rs. & J. Stud. (2024), https://jlrjs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/27.-Rishita-Yadav.pdf (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[11]S. Nivedha&SamanvithaMurali, Deepfakes in India: Unravelling India’s Legislative Uncertainty and Jurisdictional Dilemma, 11 Int l J. Emerging Res. a604 (Nov. 2024), https://tijer.org/… (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[12]Information Technology Act, No. 21 of 2000, §§ 66E, 67, INDIA CODE (2000).

[13]BharatiyaNyaya Sanhita, 2023

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, No. 45 of 2023, §§ 115–120, India Code (2023).

[14]Brennan Center for Justice, Regulating AI, Deepfakes, and Synthetic Media in the Political Arena (2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/regulating-ai-deepfakes-and-synthetic-media-political-arena (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[15]China Law Translate, Regulations on Deep Synthesis Technology (2023), https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/deep-synthesis-draft (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[16]East Asia Forum, South Korea Confronts a Deepfake Crisis (Nov. 19, 2024), https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/11/19/south-korea-confronts-a-deepfake-crisis/ (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[17]Anil Kapoor v. Simply Life India &Ors., CS (Comm) 652/2023, (Del. HC Oct. 6, 2023), available at https://www.barandbench.com (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[18]Reported by Washington Post: Joanna Slater, ‘A Living Nightmare’: Indian Journalist Targeted with Deepfake Pornography, Wash. Post (Apr. 22, 2018), https://www.washingtonpost.com (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[19]CS (OS) 27/2019, (Del. HC Jan. 23, 2019).

See Swami Ramdev v. Facebook: Delhi HC Orders Global Takedown of Defamatory Content, LiveLaw (Jan. 23, 2019), https://www.livelaw.in (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[20]W.P. No. 24041/2020, (Madras HC Oct. 28, 2020).

See Madras HC Orders Removal of Deepfake Videos of Karti Chidambaram Circulating Online, The Hindu (Oct. 29, 2020), https://www.thehindu.com (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[21]Information Technology Act, 2000, No. 21, Acts of Parliament, 2000 (India), §§ 66D, 66E, 67, 67A, 67B, 69A, 72.

[22]Copyright Act, 1957, No. 14, Acts of Parliament, 1957 (India), § 51

[23]Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986, No. 45, Acts of Parliament, 1986 (India)

[24]Representation of the People Act, 1951, No. 43, Acts of Parliament, 1951 (India)

[25]Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, No. 26, Acts of Parliament, 2023 (India)

[26]Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Advisory on Broadcast of Modified Media (Jan. 9, 2023), Press Info. Bureau, Govt. of India, https://pib.gov.in/… (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[27]Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology, Advisory on Detection and Removal of Deepfakes (Nov. 7, 2023), Press Info. Bureau, Govt. of India, https://pib.gov.in/… (last visited Aug. 25, 2025).

[28]Information Technology Act, 2000, No. 21, Acts of Parliament, 2000 (India), https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2317; Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, No. 45, Acts of Parliament, 2023 (India), https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2519; Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, No. 26, Acts of Parliament, 2023 (India), https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2537.

[29]Regulation (EU) 2021/0106, Artificial Intelligence Act, 2021 O.J. (L 206) 1 (EU), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence; Cyberspace Administration of China, Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Internet Information Services (Deep Synthesis Regulations) (2023), https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/deep-synthesis-draft.

[30]Danielle K. Citron & Robert Chesney, Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security, 107 Calif. L. Rev. 1753 (2019).

[31]Digital Services Act, Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, 2022 O.J. (L 277) 1, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-services-act_en.

[32]Tata Sons Ltd. v. Greenpeace Int ‘l &Anr., 178 (2011) DLT 705 (Del. H.C.) (India).

[33]NITI Aayog& UNESCO, Artificial Intelligence and the Need for Media and Information Literacy in India (2021), https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377488.

[34]Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2015) 5 S.C.C. 1 (India).