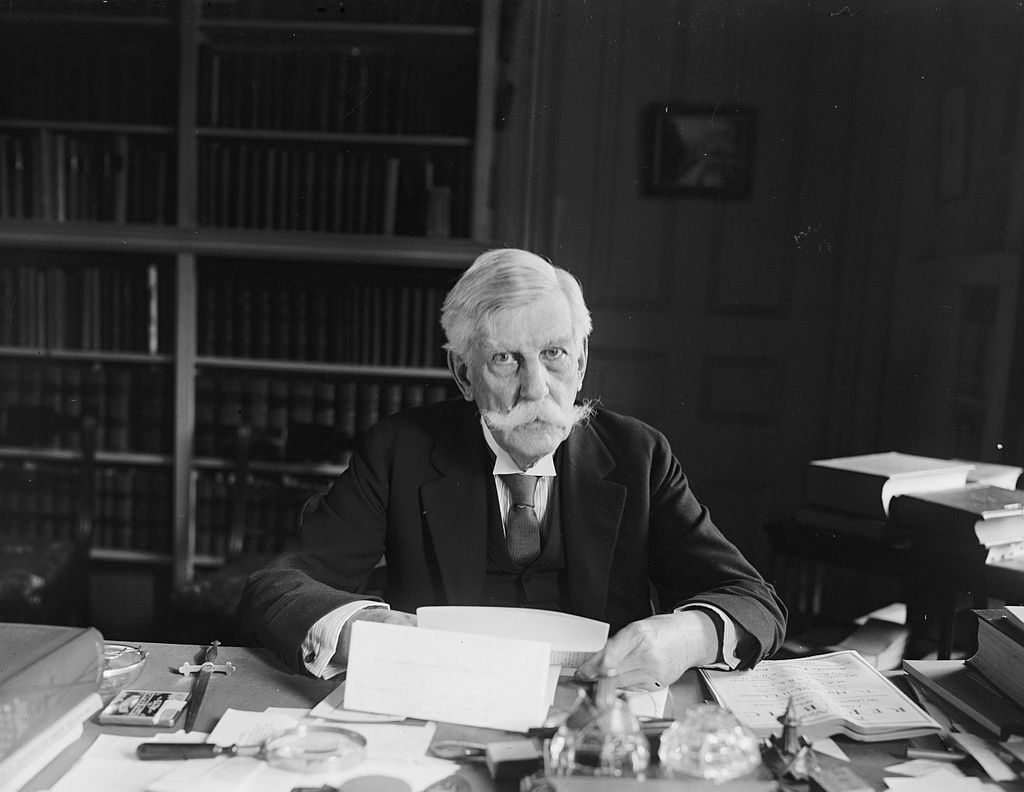

The origins of the Clear and Present Danger Doctrine, a fundamental idea for understanding the bounds of American freedom of speech and expression, are examined in this article. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. initially developed the strategy, utilising it in his 1919 ruling in the Schenck v. United States case as a means of striking a balance between the rights of the individual and the state’s duty to protect public health. This doctrine changed dramatically over time, as evidenced by the landmark 1969 case of Brandenburg v. Ohio, in which the court established stricter guidelines for when it is permissible to restrict free speech. This paper also thoroughly examines other factors, such as the impact of the seminal Texas v. Johnson (1989) case, which further contested restrictions placed on speech that is constitutionally protected and includes symbolic expressions like burning flags. Using a few of these significant cases, the paper illustrates how the Clear and Present Danger Doctrine is dynamic and captures the constantly changing relationship between individual freedom of expression and group safety.

KEY WORDS:

Freedom of speech and expressions, rights of individuals, restrictions, symbolic expressions, group safety.

INTRODUCTION:

Freedom of speech and expression as enshrined in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and similarly in Article 19 of the Indian Constitution. Nevertheless, during the course of American judicial history, these boundaries to the freedom of speech and expression have been continually tested and redefined. To distinguish between what is covered by the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech and expression, what is not, and what is outside the First Amendment’s purview, the renowned jurist Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes created the clear and present danger test in 1919. This test is a fundamental tool for understanding this distinction. A framework for weighing a person’s right to free speech and expression against the government’s interest in upholding social order, security, and discipline is provided by the clear and present danger test. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. originally developed the clear and pleasant danger test, which was first applied in the 1919 Schneck v. United States landmark decision. Under this standard, public speech can only be prohibited if it poses an immediate and clear threat to society, can incite lawlessness, or has the potential to cause substantive evils. This test seems to be simple. has, however, experienced a substantial evolution over time, mirroring modifications in the country’s social and political environment.

ORIGIN OF THE CONCEPT:

The origin of this doctrine can be. traced back to the 1919 case of Schneck vs United States, which was heard by the Supreme court of America. In a unanimous Agreement. of the court an opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wherein he quoted:

“The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.”

The Honorable Justice Holmes distinguished between the ‘clear and present danger test’ and the ‘bad tendency test’, which was well entrenched into English law and came up strongly in Gitlow v. New York (1925). Justice Holmes said, “In a time of peace, the petitioners and all their codefendants would have been within their constitutional rights.”

Therefore, it goes this way that in cases where the facts of the matter make it possible for reasonable minds to assume that for instance, the communicator intended to commit a crime banned by the state and furthermore, for it to be apparent beyond all doubt that the said communication has the capability to yield.

The bad tendency test differs from the clear and present danger test as the former involves less differentiations of circumstances. Finally, Honorable Justice Holmes finally felt that the clear-and present danger test set out and expounded upon in the Schenck case was not protective enough of fundamental rights and freedoms. Having made this statement, later in the year, in Abrams v. United States (1919), he observed that “we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions . . . unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purpose of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.”

In this quote from his dissent in the case, Hon’ble Justice Holmes emphasized the importance of safeguarding freedom of speech and expression in a democratic society. For the purpose of understanding, we shall dissect the quotation said by the Hon’ble Judge:

- “Eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions”:

- Here, the Fundamental value of free speech is stressed upon as being a cornerstone of democracy. It is argued that society should always be watchful and protective of people’s right to express their opinion and ideas without the fear of censorship or repression.

- “Unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purpose of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country”: Here, it is acknowledged that there may be situations where restrictions on free speech are necessary. The Hon’ble Judge argued that limitations on speech should only be imposed when there is an imminent and immediate threat to the lawful and essential functions of the government or the safety of the nation. In such cases, he suggests that the government may need to intervene to prevent harm or chaos.

- Emphasizing the importance of speaking freely and expressing ourselves to protect our freedom reminds us that there must be a close look at all limitations on speech to determine if they are unjustly interfering with basic rights or freedoms. Speech laws should be scrutinized to ascertain whether it struck an appropriate balance between protecting religious feelings and upholding freedom of expression.

Brandenburg v. Ohio: The “Clear and Present Danger” doctrine takes a new turn. The Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) forms an important part of the clear and present danger doctrine which has seen drastic changes in its interpretation and application by the courts. The Supreme Court examined whether the rights of individuals speech promoting violence and anarchy guaranteed under the First Amendment.

In an important decision, the Supreme Court overturned Brandenburg’s sentence by stating that the Ohio statute was incompatible with the First amendment. The Court, led by Justice William Brennan, articulated a more stringent standard for the clear and present danger test, requiring:

- Imminent lawless action: In addition, the speech should not be aimed at instigating or causing immediate unlawful action. The new interpretation, however, reduced the area of restricted speech in comparison with the previous ones.

- Likelihood of incitement: Such action will probably occur as a result of the speech. It made its case more effective and added a stronger element of causation such as providing proof that the speech was likely to create illegal actions.

The application of this doctrine changed direction with regards the speech that advocates for violence and lawlessness during the Brandenburg v. Ohio case. This ruling had several significant impacts:

- More robust protection for radical speech: This made it harder for state to control speech that is obscene even in circumstances where a person’s thoughts are controversial or offending.

- Focus on intent and context: The court highlighted, speaker`s intention and surrounding environment is an important factor for consideration when making such statements. As such, simple calls to violence alone or highly speculative advocacy would not have been prohibited.

- Debate and controversy: Whereas some people view Brandenburg as a milestone in their fight for freedom, some others argue that it brought about an unprecedented level of confusion into how the authorities could handle violent threats.

Brandenburg v. Ohio remains a significant case in the history of free speech laws and the clear and present danger doctrine, expanding the scope of protected speech and establishing a stricter standard for the application of the clear and present danger doctrine. However, the case also continues to be debated and interpreted, highlighting the ongoing tension between individual expression and collective security in a free society.

Texas vs Johnson (1989) is indeed a milestone in free speech controversy and ‘clear and present’ test. Here, the Supreme Court sought to determine which of the constitutional rights provided in the First Amendment protected this sensitive activity.

Facts of the Case-TEXAS VS JOHNSON(1989):

In 1984, during the republican national convention held in Dallas, TX, Gregory Lee Johnson, a protester burned an American flag. Johnson was then found guilty according to a Texas legislation that outlawed the destruction of a sacred relic, in this case an American flag.

The ruling of the court:

By a vote of five to four, the Supreme Court reversed Johnson’s conviction, ruling that the Texas statute violated the first amendment of the US Constitution. Justice William Brennan authored the majority opinion for the Court in this case, stating that burning a flag qualified as First Amendment-protected symbolic speech. Additionally, he maintained that the government could not censor such speech unless it displayed a clear and present danger of using force. In this regard, the court chose to apply the Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) standard of analysis, which states that speech endorsing acts of violence or breaking the law must promptly incite unlawful behaviour that has a high probability of leading to it. However, because the Act was deemed to be “offensive” and “provocative,” it did not violate the strict standard. Thus, the Court determined that the Act prohibiting flag burning on public land was unconstitutional.

In Texas v. Johnson, the Court upheld the First Amendment’s protection of the highly controversial right to burn that flag. The case underscored the significance of symbolic speech, recognising that one may articulate forceful messages protected under the First Amendment through actions. Additionally, it demonstrated how challenging it is to apply the clear and present danger test to concepts like flag burning.

Indian Scenario:

The restriction in the interest of public order to be a reasonable one must be proximately connected with it, not distantly construed imaginary or hypothetical or too remote from its effect on public order,” Justice Subba Rao said in Superintendent, Central Prison v. Ram Manohar Lohia, creating the “proximate nexus” test, an Indian version of the Clear and Present Danger test that restricts free speech on grounds of public order.

The criteria for prohibiting speech that could disturb public peace were established in this case by the Supreme Court, also known as the Hon’ble Apex court. The Hon’ble Apex Court outlined the following fundamental components for those tests:

a. Close connection to public order

b. The possible disturbance must not be far away

The legal guidelines established in the aforementioned case are crucial in determining how much speech disturbs public order. The test stipulates that there must be a clear and direct connection between the speech in question and the threat to public order. Speech must have the capacity to incite public disorder and there must be a clear and immediate connection between the speech and the potential disturbance. Therefore, it clearly mandates that any potential disturbance of public order must be evident and predictable rather than remote. This suggests that speech needs to be able to seriously and immediately disrupt public order.

This standard guarantees the preservation of public order and peace while upholding the right to free speech and expression.

The cases of Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962) and S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989) are similar in that they make use of the clear and present danger test or the proximate nexus test, as defined by Justice Subba Rao in the Indian context.

Conclusion:

The path followed by the Clear and Present Danger Doctrine offers a notable way to balance the government’s duty to maintain public order with society’s right to free speech. This doctrine began with the seminal case of Schenck v. United States and underwent dynamic transformations in the cases of Brandenburg v. Ohio and Texas v. Johnson. It was even applied in the Indian context, where it was known as the “proximate nexus test.” The Brandenburg ruling, in particular, stipulated that for speech to be justified in being restricted, it must pose a serious threat of immediate incitement to unlawful action.

The Texas v. Johnson case also brought to light the difficulties in ap plying the Clear and Present Danger standard to expressive issues expressed symbolically.

As democratic countries attempt to find a balance between individual liberties and public safety, this doctrine continues to spark discussions about how to interpret and apply it. This doctrine’s journey embodies a persistent challenge: striking a careful balance between promoting social cohesion and safeguarding the fundamental right to free speech.

References

[i] Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/249/47/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[ii] Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925), Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/268/652/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[iii] Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919), Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/250/616/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[iv] Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/395/444/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[v] Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989), Justia Law, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/491/397/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[vi] India, superintendent central prisons v. Ram Manohar Lohia, 1960 Air 633, Global Freedom of Expression, https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/laws/india-superintendent-central-prisons-v-ram-manohar-lohia-1960-air-633/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[vii] Kedar Nath Singh v state of bihar, Global Freedom of Expression (2021), https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/cases/nath-singh-v-bihar/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[viii] India, S. Rengarajan and Ors V. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), 2 SCC 574, Global Freedom of Expression, https://globalfreedomofexpression.columbia.edu/laws/india-s-rengarajan-and-ors-v-p-jagjivan-ram-1989-2-scc-574/ (last visited Dec 10, 2023).

[ix] Article 19 of the Indian constitution-https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1218090/

[x]https://www.livelaw.in/columns/reading-the-path-of-the-law-on-justice-holmes-birthday-170795

AUTHOR:

JAYMEET JOSHI

CHRIST (DEEMED TO BE) UNIVERSITY, DELHI NCR.