his research study investigates the multidimensional evolution of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, from the Instrument of Accession to its subsequent abrogation and the resulting post-abrogation landscape. The enactment of Article 370, which was founded in the historical circumstances surrounding the signing of the Instrument of Accession in 1947, presented Jammu and Kashmir with a special constitutional position. The article goes into the legal complexities, political dynamics, and socioeconomic ramifications of Article 370, offering light on the constitutional provisions, presidential decrees, and challenges and controversies that have arisen as a result of it.

The research follows the political changes within and outside the region, investigating the internal and external factors that influenced the discourse surrounding Article 370. The study methodically analyses the chain of constitutional amendments and legislative acts that led to the repeal of Article 370, elucidating the immediate and long-term consequences of this historic decision. Furthermore, it explores the administrative reorganisation of Jammu and Kashmir into Union Territories, as well as the post-reorganization socio-political landscape, focusing on security, human rights, and public mood.

This research paper integrates historical, legal, and political viewpoints to present a thorough understanding of Article 370’s growth. It adds to the scholarly conversation by unraveling the complexities of its path, providing insights into the development of the region’s constitutional and political landscape, and pondering probable future possibilities.

Keywords

Article 370, Jammu and Kashmir, India, accession, autonomy, abrogation, conflict, identity, reconciliation.

Introduction

The story of Article 370 is intricately woven with the fraught history of Jammu and Kashmir. This exception provision, which grants the state enormous autonomy inside the Indian Union, has sparked heated debate and controversy for decades. Its evolution, from an instrument of accession to a point of contention and ultimately, abrogation, reflects the complex interplay of political aspirations, cultural identities, and security concerns in the region.

Research Methodology

- Historical Research

Reconstructing the historical story that led to the adoption of Article 370 through the use of historical records, archival resources, and sources.

- Legal Evaluation

Completing a thorough legal study of Article 370-related constitutional clauses, modifications, and court rulings.

- Policy Analysis

Assessing the political developments and policy choices that shaped the outcome of Article 370, including its repeal and the ensuing modifications to the law.

- Evaluation via Comparison

Making analogies with other areas and constitutional clauses to put the particularities and difficulties of Article 370 in perspective.

Review of Literature

- Historical Perspectives

An analysis of historical narratives and viewpoints about Jammu and Kashmir’s admission into India, covering the events leading up to the Constitution’s insertion of Article 370.

- Legal Dimensions

Analyzing the legal interpretations and arguments around Article 370, including significant court rulings and the views of constitutional experts regarding the law’s applicability and consequences.

- Political Aspects

Examining how Article 370 has changed politically, how it has influenced the relationship between the federal government and the state of Jammu and Kashmir, and how political choices have affected the law’s future.

- Consequences for Socio-Economy

Evaluating Article 370’s socioeconomic impacts on Jammu and Kashmir’s population, taking into account how it may affect social dynamics, development, and governance.

Historical Context

Jammu and Kashmir is known as a “paradise on earth” due to its picturesque beauty and strategic location. The state has a long history and has gone through several stages. One may argue that 1846 was a watershed moment in J&K history. The first Anglo-Sikh war had just ended this year, with the British emerging triumphant. Raja Gulab Singh, who had previously administered Jammu under the Sikh Empire’s suzerainty, was awarded an additional area of Kashmir to be managed under the British Government’s suzerainty. As a result, the Dogra dominion was established in Kashmir, with Maharaja Gulab Singh as the first Dogra king.1

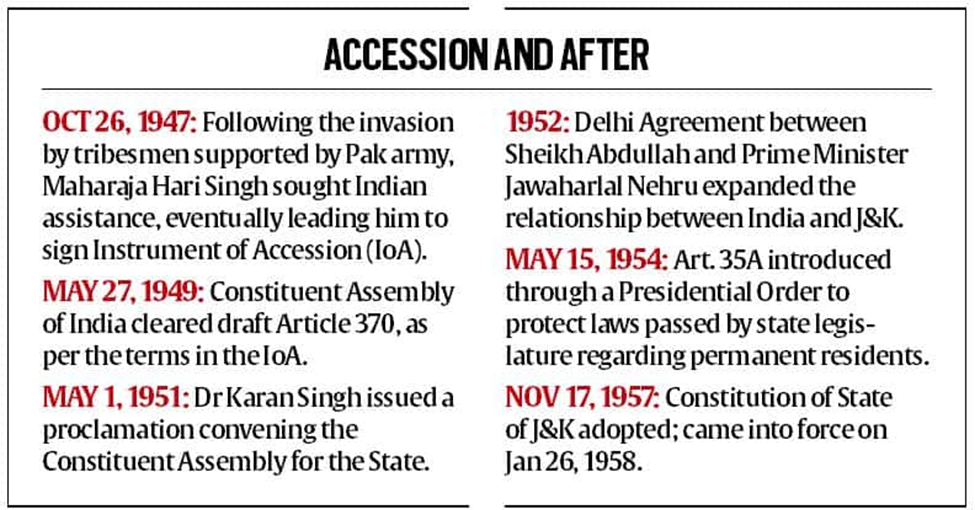

In 1927, Maharaja Hari Singh, the last Dogra monarch of Jammu and Kashmir, enacted legal protections for the people of Jammu and Kashmir, stating that no ‘foreign’ could possess land in the state or hold government jobs. This is the underlying idea that gave rise to Article 35A.2 On August 15, 1947, India gained independence from British dominion, but with the division of British India. Lord Mountbatten, India’s final governor-general, outlined the partition plan during the time in June 1947 known as “Mountbatten’s Partition Plan.”

Following India’s independence and religious partition, Jammu and Kashmir was one of 562 states that fell under the suzerainty of the British Crown, and it was left to decide its future. All of these states were restored to full sovereign and independent status almost immediately, with the choice of joining one of the two dominions or staying independent. Even while the will of the people and geographical location were not legally binding on the princely states, they were the fundamental basis for the states’ choice. Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of the British Empire, submitted two documents to the rulers: the Instrument of Accession and a Standstill Agreement, which provided for the temporary continuation of agreements and arrangements in subjects of common concern between the states and the dominion of India. Except for Hyderabad, Junagadh, and Kashmir, all of these states joined one of the dominions soon after independence.

The state of Jammu and Kashmir had created a Standstill Agreement with the government of Pakistan regarding the maintenance of the current system concerning posts and telegraphs, etc., so Kashmir could surpass either of the two dominions or remain independent. The Maharaja, who wanted to preserve and safeguard his princely powers, was hesitant to sign an accession treaty with either India, which was aiming for a democratic and anti-feudal future, or Pakistan, which had a Muslim majority. Sheikh Abdullah, who was released from prison in September 1947, openly announced his desire for independence, saying that if the state declared accession to India or Pakistan, he would raise the banner of insurgency. This period of indecision coincided with several other almost simultaneous events, including communal unrest in Jammu caused by the movement of refugees from West Punjab into Jammu, the Poonch revolt against the Maharaja, and armed tribals entering the state with the support of Pakistan authorities, causing the Maharaja to submit a frantic distress plea to the government of India.

Instrument of Accession

The armed tribals from the North West Frontier Province have entered Kashmir. Subsequently, V.P. Menon met with the Maharaja in Srinagar on October 26, 1947, and the two traveled to Delhi, where Menon informed the defense committee that the only rationale for deploying troops into an independent country was accession and that it should be contingent on finding the people’s will. Following this summit, it was decided that Jammu and Kashmir’s accession should be accepted on the condition that a plebiscite be held in the state when the law and order situation allowed it. Menon added that Sheikh Abdullah wholeheartedly backed it. On October 26, 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, the last ruler of Jammu and Kashmir, signed the Instrument of Accession to the Dominion of India. The Maharaja agreed to give the Parliament authority over three subjects while limiting the Union’s powers to Foreign Affairs, Defence, and Communications.3

Article 370 was a constitutional acceptance of the circumstances described in the Instrument of Accession, reflecting the two parties’ contractual rights and obligations.

The Indian Constitution came into effect on January 26th, 1950. Three main foundations were established by Article 370. In general, Article 370 stated that India would not pass laws in Jammu and Kashmir that exceeded the scope of the Instrument of Accession without the ‘concurrence’ of its government. It went on to add that, except for Article 1, which declares India a “Union of States,” and Article 370, no provision of the Constitution applies to Jammu and Kashmir. The President of India may, with “modifications” or “exceptions,” apply any article of the Constitution to this State, but only after “consultation with the State Government.” Third, Article 370 could not be changed or repealed unless the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly concurred. Following that, President Rajendra Prasad issued his first order under Article 370, the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 1950, establishing the scope and extent of the powers that the Parliament would have in Jammu and Kashmir. The act of Accession stipulated that the Union would govern the State’s exterior affairs, communications, and defense. The President’s directive specified the specific issues that would fall under these categories. The Order also included Schedule II, which stated the updated Constitutional provisions that would apply to the State.

Both the Accession instrument and Article 370 were regarded as provisional measures. The autonomy given by Article 370 was conditional on the constituent assembly of the state drafting its constitution.

Abrogation of Article 370

On August 6, 2019, India saw a historic event with the deletion of Article 370, a constitutional provision that had provided the state of Jammu and Kashmir special autonomy since its entrance into the Indian Union in 1947. This major decision, implemented by a presidential decree and parliamentary resolution, signified a seismic upheaval in the region’s constitutional and political landscape.

The constitutional changes in Jammu and Kashmir were brought about by Presidential Order 272, a statutory resolution in parliament recommending that the president deactivate Article 370, and the J&K Reorganisation Act, which divided the state into Union Territories of Ladakh, which did not have a legislature, and Jammu and Kashmir, which did have a legislature but was weakened by two all-powerful Lieutenant Governors, allowing the Central Government to directly rule the state.

The administration of Jammu and Kashmir has granted its consent to the presidential instruction. However, Jammu and Kashmir were under the President’s Rule, and consent received came from the Governor, who served as a representative of the federal government. The Centre used its consent to amend the constitution on this occasion. This was a violation of Article 370 of the constitution, which requires the J&K Constituent Assembly’s recommendation before any amendments are made. However, the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly ceased to exist in 1957.the the

The President used Article 370 modification powers by issuing the Constitution (Application to Jammu and Kashmir) Order, 2019, which replaced the state’s Constituent Assembly with the state’s Legislative Assembly, eliminating the constitutional requirement to convene a newly elected Constituent Assembly to decide the future of Article 370. Since the President’s authority under Article 356 was in effect in Jammu and Kashmir, the administration argued that Parliament could function as the Legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir, while urging that Article 370 be repealed.

The Presidential order amends Article 376 by substituting “legislative Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir” for “Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir” and “government of Jammu and Kashmir” for “governor of Jammu and Kashmir acting on the aid and advice of the council of ministers.” The Presidential order also necessitates the approval of the state government.

Article 370 Abrogation Case

A group of senior lawyers, including Kapil Sibal, Gopal Subramanium, Rajeev Dhavan, Dushyant Dave, and Gopal Sankaranarayanan, filed several petitions challenging the Presidential Orders of August 5 and 6, 2019, as well as the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019 (2019 Act) as unconstitutionally drafted. The key legal issues raised in the proceedings are whether the status of J&K became permanent after the Constituent Assembly refrained from making any decision on Article 370 before its dissolution in 1957, and whether the latter effectively prevents the Union government from unilaterally changing the State’s relationship with India, and whether the initially ‘temporary’ nature of the provision has now acquired a permanent character.4 The petitioners used the “doctrine of colorable legislation,” which states that “what cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly.” According to the petitioners, the President has implicitly modified Article 370, a constitutional provision, without the approval of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly.

The government, represented by Attorney-General R. Venkataramani, Solicitor-General Tushar Mehta, and counsel Kanu Agrawal, claimed that the abrogation was necessary to completely incorporate Jammu and Kashmir into the Indian Union. It also promised that Jammu and Kashmir’s Union Territory status was only a “temporary phenomenon” and that it would be restored to full statehood.

On August 28, 2019, the Supreme Court of India accepted multiple petitions challenging the repeal of Article 370 and the subsequent split of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories, forming a five-judge bench to hear the case.

JUDGEMENT

On December 11, 2023, the Supreme Court of India delivered a major decision to remove Articles 370 and 35A. The Court’s decision has protected India’s sovereignty and integrity, which is something that every Indian values. The Supreme Court stated that the decision to repeal Article 370, which abolished the former state of J&K’s unique status, was made to strengthen constitutional unity rather than disintegration. The Court also acknowledged that Article 370 was not permanent in nature because it served a transitory purpose, establishing a Constituent Assembly of J&K to create the State Constitution and was intended to facilitate J&K’s integration into the Union of India, given the state’s war-like circumstances in 1947. The court affirmed the proclamations by citing the landmark 1994 decision in ‘SR Bommai v Union of India, 19945,’ which dealt with the Governor’s powers and restrictions under the President’s rule.

The CJI stated that the governor can undertake “all or any” duties of the state legislature and that such action should only be tried in extreme circumstances. The court upheld the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, which splintered the Union Territory of Ladakh from the state of J&K. The court declared that J&K’s statehood should be restored as soon as possible and ordered elections for J&K’s legislative assembly be held by September 30th, 2024. In his concurring opinion, Justice Kaul advocated the construction of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, similar to the one created in South Africa following apartheid, to investigate human rights crimes committed by both state and non-state actors in Jammu and Kashmir during the 1980s.

The judgment of the Supreme Court played a crucial role in promoting the principles of unity and good governance in the country.

Implications and beyond

The repeal of Article 370 in August 2019 has a significant and complex influence on the social environment of Jammu and Kashmir. The effects, however, are complex and contested, with diverse perspectives and ongoing debates. An exploration of some key social implications is as follows:

- Identity and Belonging:

- Kashmiri identity: The abrogation has intensified feelings of alienation and marginalization among many Kashmiris, particularly in the Muslim-majority Valley. They perceive it as an assault on their distinct identity and cultural autonomy.

- National integration: Proponents of the abrogation argue it fosters greater national integration by removing barriers and promoting a unified Indian identity. However, critics argue it imposes a dominant national identity, disregarding the unique cultural and historical context of Kashmir.

- Fear and uncertainty: The abrogation has created a climate of fear and uncertainty in Kashmir. Concerns regarding demographic changes, cultural erosion, and potential discrimination have led to anxiety and insecurity among many communities.

- Political Participation and Representation:

- Dissatisfaction with political processes: The abrogation has further eroded trust in the political process, particularly among Kashmiris who feel their voices are unheard and their concerns ignored.

- Limited political space: Restrictions on political activities and the detention of political leaders have further restricted democratic space and stifled dissent, leading to frustration and resentment.

- Emergence of new political actors: The abrogation has created space for new political actors, both within and outside Kashmir, to advocate for their visions of the region’s future, potentially shaping future political dynamics.

- Bifurcation: On August 9, 2019, the Union Parliament passed the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, which divided the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories. The two new Union Territories are Jammu and Kashmir, which retains its legislative assembly, and Ladakh.4

- Socioeconomic Development and Opportunities:

- Potential for development: The Indian government argues the abrogation will bring economic benefits and development opportunities to Kashmir by removing restrictions on investment and integration with the wider Indian economy. However, critics raise concerns about unequal access to these benefits and the potential exploitation of resources.

- Livelihoods and economic uncertainty: The abrogation has disrupted traditional economic activities in Kashmir, particularly tourism, impacting livelihoods and exacerbating existing economic disparities.

- Educational and healthcare access: Concerns remain about the potential impact on access to quality education and healthcare, particularly in remote areas, as the integration process unfolds.

- Gender and Social Inequalities:

- Impact on women: The abrogation raises concerns about the potential impact on women’s rights and safety, particularly in the context of increased militarization and social conservatism.

- Marginalization of vulnerable communities: The abrogation may further marginalize already vulnerable communities, such as religious minorities and Dalits if their specific needs and concerns are not adequately addressed.

- Potential for social tension: The abrogation could exacerbate existing social divisions and tensions along the lines of religion, ethnicity, and class, posing challenges to social harmony and stability.

- Long-term Trajectory:

- Reconciliation and healing: The long-term social impact of the abrogation will depend on the Indian government’s approach to reconciliation and healing. Building trust, addressing grievances, and promoting inclusive dialogue are crucial for long-term stability and peace.

- Shifting demographics: Concerns about potential demographic changes due to the abrogation’s provisions on domicile and land ownership could further complicate social dynamics and identity politics in the region.

- Civil society organisations play an important role in advocating for human rights, promoting discussion, and assisting vulnerable populations in dealing with the social consequences of abrogation.

The social implications of abrogating Article 370 are far-reaching and complex. While some view it as a step towards progress and integration, others perceive it as a threat to Kashmiri identity and autonomy. Addressing the concerns of marginalization, building trust, and fostering inclusive dialogue are crucial steps towards navigating the social ramifications of this decision and working towards a peaceful and equitable future for Jammu and Kashmir.

Conclusion

The saga of Article 370, from its contested genesis in the Instrument of Accession to its dramatic abrogation in 2019, stands as a poignant testament to the complexities of nation-building, identity politics, and the evolving nature of federalism in India. It has been the focus of heated debate, legal challenges, and political manoeuvres, shaping the contours of Kashmiri identity and its relationship with the Indian state.

The 2019 abrogation, a bold move by the Indian government, marked a watershed moment. Proponents hailed it as a necessary step for national integration and security, while critics condemned it as a violation of constitutional principles and J&K’s special status. The legal challenges that followed, culminating in the Supreme Court’s verdict, answered the complex questions of federalism, autonomy, and the nature of the Union of India that Article 370 has forced us to confront.

The evolution of Article 370 serves as a stark reminder that India’s journey towards a truly united and equitable nation is still ongoing. While the abrogation has closed one chapter, the questions it raised about identity, autonomy, and the nature of the Indian Union remain open-ended. As we move forward, it is crucial to engage in a nuanced and inclusive dialogue, acknowledging diverse perspectives and seeking solutions that respect both the aspirations of the Kashmiri people and the integrity of the Indian nation. Only then can we truly move beyond the legacy of Article 370 and build a future where all citizens feel secure, empowered, and part of a shared national narrative.

Author: Sharanya Agarwal, 3rd year student of Amity University, Lucknow.